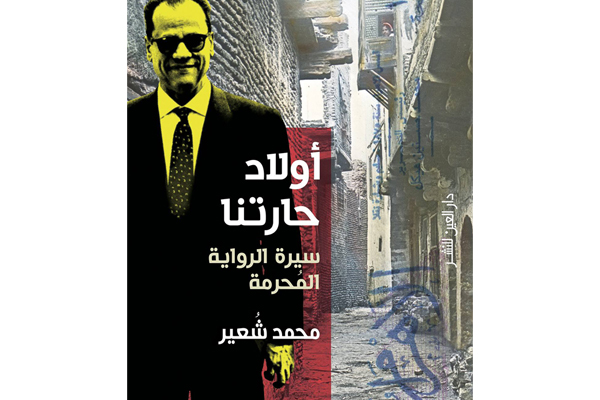

Mohamed Shoair, Abnaa Al-Gabalawi: Sirat Al-Riwaya Al-Muharramah (Sons of Gebelawi: Biography of the Forbidden Novel), Cairo: Al-Ain, 2018. pp250

Reviewed by Nahed Nasr

In his new book, Mohamed Shoair focuses on the most controversial novel by the late Nobel laureate Naguib Mahfouz (1911-2006), Children of Gebelawi (first published in book form by Dar Al-Adab in Beirut in 1962 and only illegally distributed in Egypt). A prominent cultural journalist and the managing editor of Egypt’s most popular dedicated literary publication, Akhbar Al-Adab, Shoair has been known to play the role of historian of contemporary Arabic literature with rare aptitude.

Here, in 18 chapters, most of which work equally well as standalone articles, Shoair deals with every aspect of Gebelawi, beginning with the circumstances surrounding the release of the book that caused Mahfouz the greatest trouble (though it is also said to be the one that won him the Nobel prize in 1988). Banned in Egypt for allegorically personifying God, it wasn’t published in Egypt (by Dar El Sherouk) until 2006, a few months before Mahfouz’s death and many decades after it was serialised in Al-Ahram in 1959. The book is also behind the 1994 attempt on Mahfouz’s life by extremist followers of Omar Abdel-Rahman who almost certainly had not read it. But it was first objected to by the allegedly moderate institution of Al-Azhar, which called for banning it in 1960 and again in the 1980s. In many ways it is the ideal platform for analysing the dynamics of censorship in Egypt – another of Shoair’s favourite topics – taking into account its official, religious and social dimensions. Who, Shoair also seems to be asking in this book, are freedom of expression’s gatekeepers?

Typically of Shoair, the book gathers together interviews, articles, letters and other archival material like puzzle pieces forming a comprehensive picture. According to the author himself, the presentation follows the model of a novel: “a literary narrative that happens to employ criticism as its method”. Shoair dedicate the book to Taha Hussein (1889-1973) and Nasr Hamed Abu-Zeid (1943-2010), two pillars of Arab enlightenment who suffered censorship and religious persecution. Maintaining neutrality and asking rather than answering questions, Shoair leaves his subjective contribution to the last chapter, “a delayed introduction”, as he calls it. “But maybe I put it where it should be.” One of two epigraphs is something Kamal Abdel-Gawwad, one of the characters in Mahfouz’s Cairo Trilogy says: “I am a tourist in a museum where I own nothing, a mere historian not knowing where to stand.”

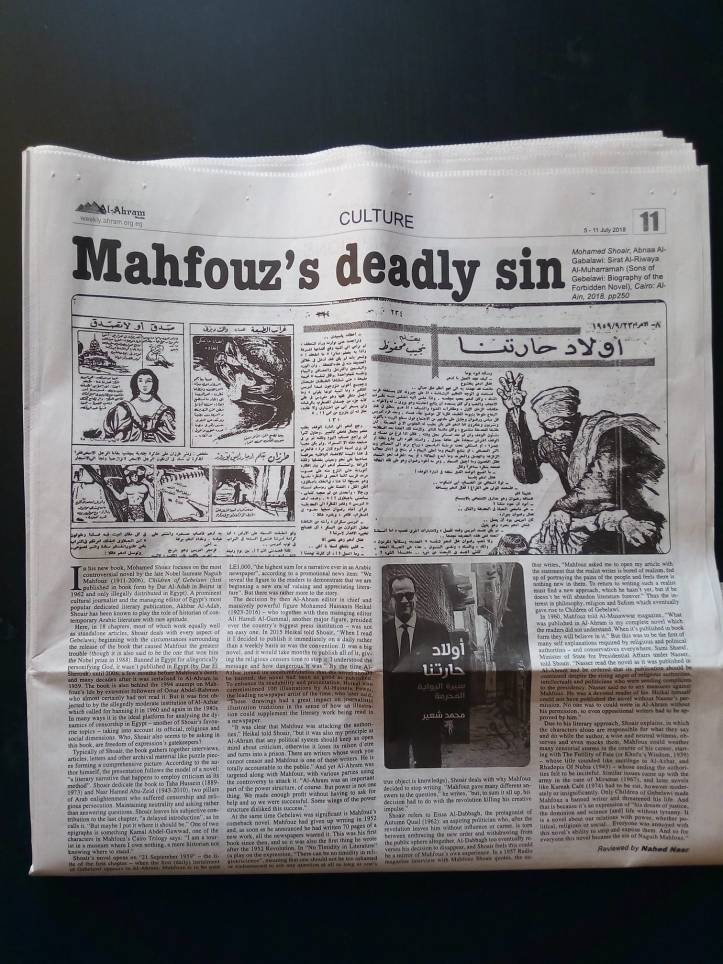

Shoair’s novel opens on “21 September 1959” – the title of the first chapter – when the first (daily) instalment of Gebelawi appears in Al-Ahram; Mahfouz is to be paid LE1,000, “the highest sum for a narrative ever in an Arabic newspaper”, according to a promotional news item: “We reveal the figure to the readers to demonstrate that we are beginning a new era of valuing and appreciating literature”. But there was rather more to the story.

The decision by then Al-Ahram editor in chief and massively powerful figure Mohamed Hassanin Heikal (1923-2016) – who together with then managing editor Ali Hamdi Al-Gammal, another major figure, presided over the country’s biggest press institution – was not an easy one. In 2015 Heikal told Shoair, “When I read it I decided to publish it immediately on a daily rather than a weekly basis as was the convention. It was a big novel, and it would take months to publish all of it, giving the religious censors time to stop it. I understood the message and how dangerous it was.” By the time Al-Azhar issued its recommendation that the novel should be banned, the novel had been as good as published. To enhance its readability and presentation, Heikal also commissioned 100 illustrations by Al-Hussein Fawzi, the leading newspaper artist of the time, who later said, “Those drawings had a great impact on journalistic illustration traditions in the sense of how an illustration could supplement the literary work being read in a newspaper.

“It was clear that Mahfouz was attacking the authorities,” Heikal told Shoair, “but it was also my principle at Al-Ahram that any political system should keep an open mind about criticism, otherwise it loses its raison d’etre and turns into a prison. There are writers whose work you cannot censor and Mahfouz is one of those writers. He is totally accountable to the public.” And yet Al-Ahram was targeted along with Mahfouz, with various parties using the controversy to attack it. “Al-Ahram was an important part of the power structure, of course. But power is not one thing. We made enough profit without having to ask for help and so we were successful. Some wings of the power structure disliked this success.”

At the same time Gebelawi was significant is Mahfouz’s comeback novel. Mahfouz had given up writing in 1952 and, as soon as he announced he had written 70 pages of a new work, all the newspapers wanted it. This was his first book since then, and so it was also the first thing he wrote after the 1952 Revolution. In “No Timidity in Literature” (a play on the expression, “There can be no timidity in religion/science”, meaning that one should not be too ashamed or embarrassed to ask any question at all as long as one’s true object is knowledge), Shoair deals with why Mahfouz decided to stop writing. “Mahfouz gave many different answers to the question,” he writes, “but, to sum it all up, his decision had to do with the revolution killing his creative impulse.”

Shoair refers to Eissa Al-Dabbagh, the protagonist of Autumn Quail (1962): an aspiring politician who, after the revolution leaves him without influence or career, is torn between embracing the new order and withdrawing from the public sphere altogether. Al-Dabbagh too eventually reverses his decision to disappear, and Shoair feels this could be a mirror of Mahfouz’s own experience. In a 1957 Radio magazine interview with Mahfouz Shoair quotes, the author writes, “Mahfouz asked me to open my article with the statement that the realist writer is bored of realism, fed up of portraying the pains of the people and feels there is nothing new in them. To return to writing such a realist must find a new approach, which he hasn’t yet, but if he doesn’t he will abandon literature forever.” Thus the interest in philosophy, religion and Sufism which eventually gave rise to Children of Gebelawi.

In 1960, Mahfouz told Al-Musawwar magazine, “What was published in Al-Ahram is my complete novel which the readers did not understand. When it’s published in book form they will believe in it.” But this was to be the first of many self explanations required by religious and political authorities – and conservatives everywhere. Sami Sharaf, Minister of State for Presidential Affairs under Nasser, told Shoair, “Nasser read the novel as it was published in Al-Ahram and he ordered that its publication should be continued despite the rising anger of religious authorities, intellectuals and politicians who were sending complaints to the presidency. Nasser said no to any measures against Mahfouz. He was a devoted reader of his. Heikal himself could not have published the novel without Nasser’s permission. No one was to could write in Al-Ahram without his permission, so even oppositional writers had to be approved by him.”

Due to his literary approach, Shoair explains, in which the characters alone are responsible for what they say and do while the author, a wise and neutral witness, observes and even mocks them, Mahfouz could weather many censorial storms in the course of his career, starting with The Futility of Fate (or Khufu’s Wisdom, 1939) – whose title sounded like sacrilege to Al-Azhar, and Rhadopis Of Nubia (1943) – whose ending the authorities felt to be inciteful. Similar issues came up with the army in the case of Miramar (1967), and later novels like Karnak Café (1974) had to be cut, however moderately or insignificantly. Only Children of Gebelawi made Mahfouz a banned writer and threatened his life. And that is because it’s an expression of “his dream of justice, the dominion and science [and] life without tyranny. It is a novel about our relations with power, whether political, religious or social… Everyone was annoyed with this novel’s ability to strip and expose them. And so for everyone this novel became the sin of Naguib Mahfouz.”

This article was first published in Ahram Weekly 5 July 2018